Canada

The Canadian city betting on recycling rare earths for the energy transition

As countries scramble to secure critical minerals, Kingston’s burgeoning clean tech ecosystem is attracting startups to create circular supply chains and reduce reliance on China

Chris Arsenault

Author

Ian Willms / Panos Pictures

Photos & video footage

Canada

The Canadian city betting on recycling rare earths for the energy transition

As countries scramble to secure critical minerals, Kingston’s burgeoning clean tech ecosystem is attracting startups to create circular supply chains and reduce reliance on China

Chris Arsenault

Author

Ian Willms / Panos Pictures

Photos & video footage

Inside a sprawling warehouse in Kingston, Ontario, in Central Canada, a forklift beeps past huge cardboard boxes full of discarded electric vehicle motors, stripped down copper wires and the rusty brown innards of old MRI machines.

All await the same fate: being crunched into a powder so their critical minerals can be extracted.

As countries scramble to secure supplies of the raw materials they need to manufacture wind turbines, batteries and other technologies key to preventing runaway climate change, this facility run by local startup Cyclic Materials is part of an emerging industry: creating a circular economy for critical energy transition minerals.

“Recycling means you get [back] the high-value stuff,” said Ahmad Ghahreman, CEO of the company, which has received funding from electric vehicle heavyweights like BMW.

The roll-out of clean energy technologies is fuelling rocketing demand for critical minerals. But mining these minerals can be a dirty process which is concentrated in a handful of countries. In addition, China overwhelmingly dominates the processing of critical minerals. Concerned about this concentration, Western countries are actively seeking ways to diversify their supply chains and reduce their dependence on Beijing.

Emerging recycling technologies offer a sustainable way to shore up the supplies the world needs and reduce pressure to expand mining. For Canada, it is also part of a plan to ease Chinese imports.

Cyclic Materials’ current operations are small, but the buzz around the company is far-reaching. “We have a lot of pressure to expand… We are very excited,” said Ghahreman, a former chemistry professor at Kingston’s Queen’s University, one of Canada’s top engineering schools.

As Canada ramps up efforts to scale its supply chain to manufacture electric vehicles (EVs), Kingston’s ecosystem of cleantech companies is poised to play a pivotal role in offering alternatives to China’s grip on rare earths processing.

Rare vision

At the Cyclic Materials plant in an industrial area, a conveyor carries metal shavings from shredded EV motors and other electronics. Amid deafening screeches of tearing metal, the shavings are broken down through a patented process to create a fine charcoal-coloured powder that the company calls Mag-Xtract, which contains rare earths.

With names like dysprosium, neodymium and terbium, there are 17 rare earth elements. These are essential for building wind turbines, EVs, advanced semiconductors, and virtually all other clean technologies, which countries need to transition their economies away from fossil fuels to net zero emissions by 2050.

Wind turbines being recycled at Cyclic Materials

Cyclic Materials’ vice president for engineering & technology Alex Forstner explains how recycled magnets are reduced into Mag-Xtract

Cyclic Materials has ambitious plans to change that. By 2035, it aims to open half a dozen rare earths recycling plants across North America, creating a regional supply chain that would enable the production of 6.3 million motors for EVs.

When it comes to recycling rare earth elements, “I think Kingston will be on the map because no one is on the map,” said Boyd Davis, co-owner of Kingston Process Metallurgy (KPM), a stalwart laboratory-for-hire which works with Cyclic Materials and supports other rare earths processing companies to set up in the city.

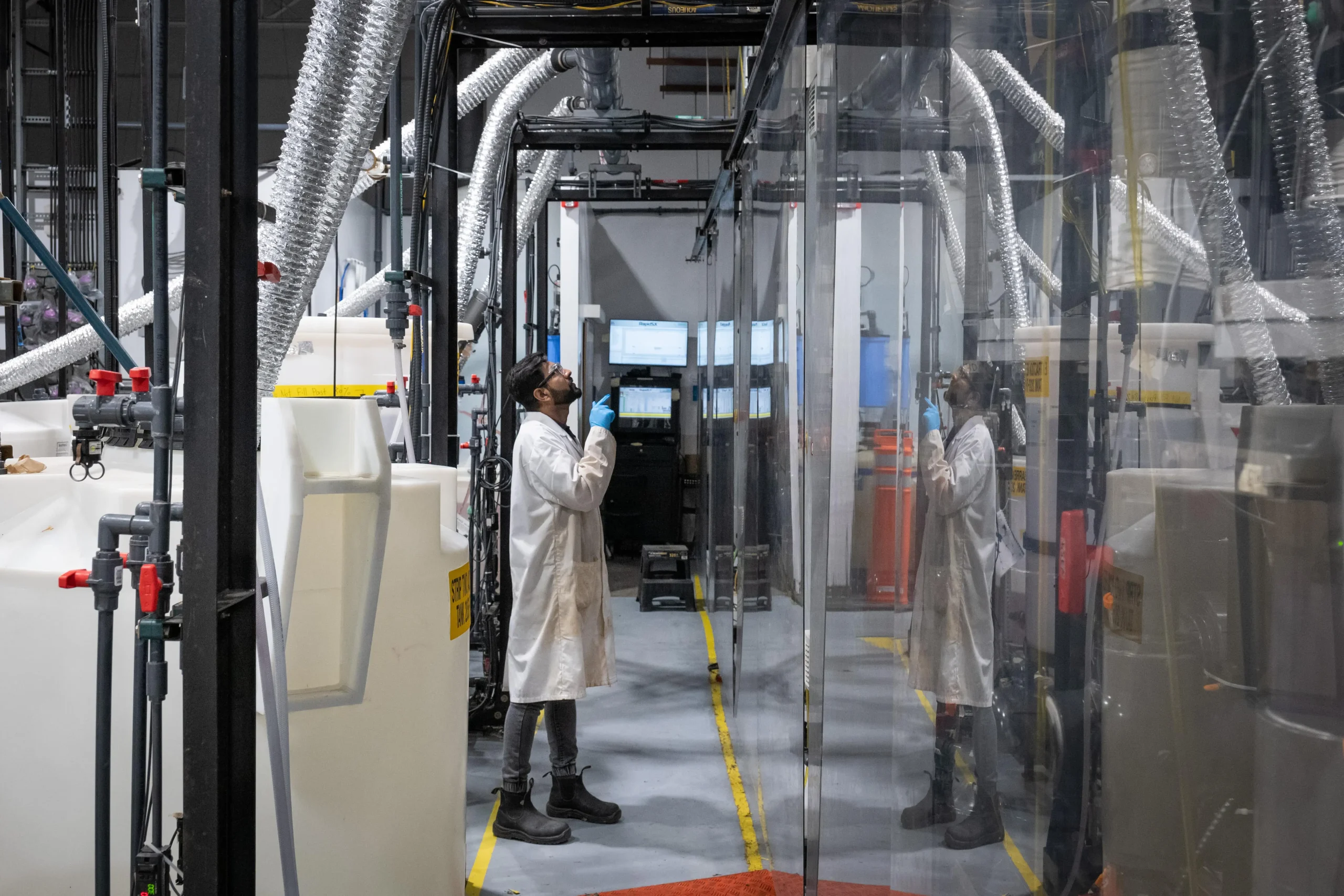

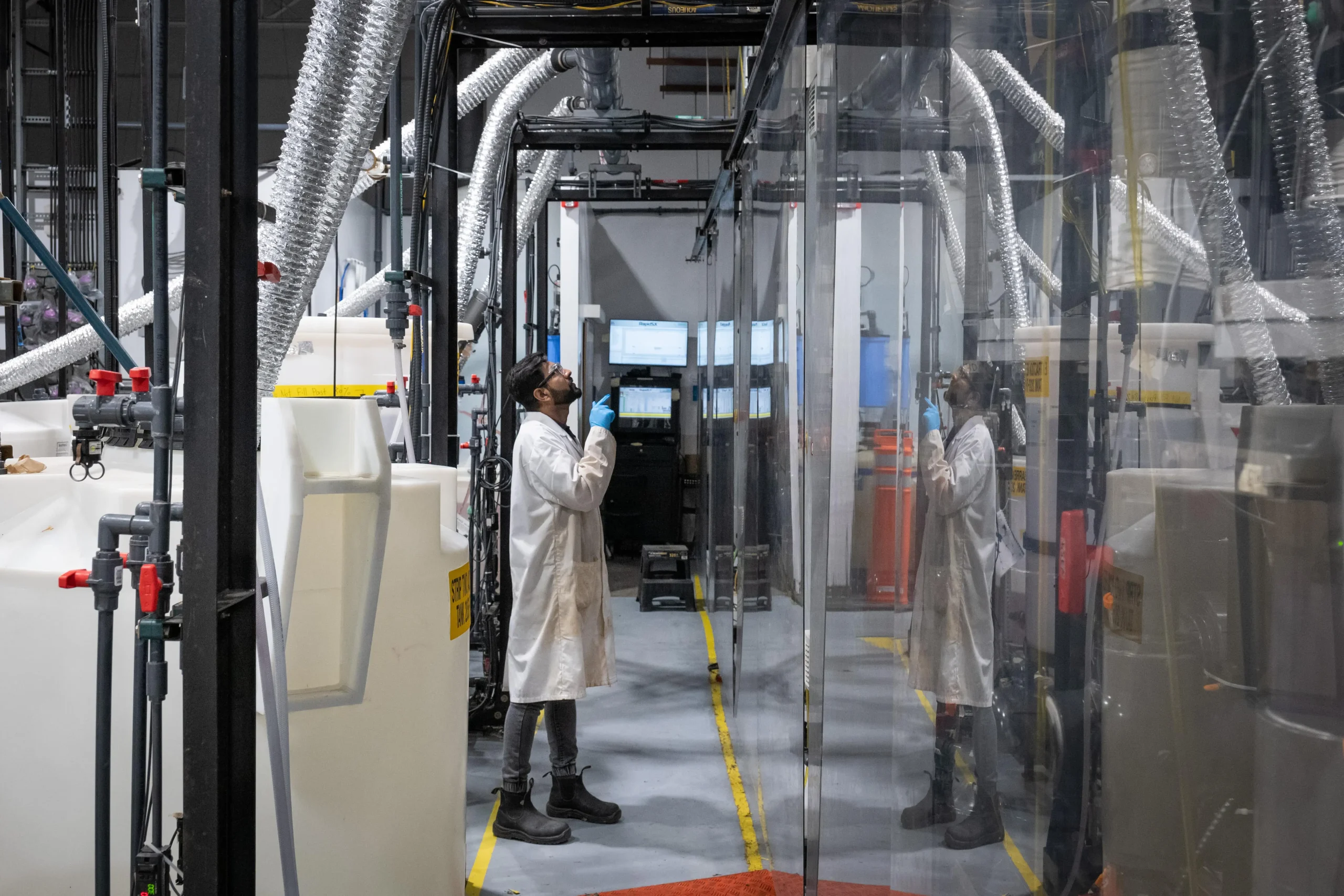

Inside a KPM lab in Kingston

Safety gear at a KPM lab in Kingston

Staff working at a KPM lab in Kingston

Challenging China’s rare earth dominance

China currently mines about 60% of the world’s rare earth elements and has near total dominance in processing them, refining nearly 90% of the world’s supplies, IEA data shows.

The country produces about 93% of the world’s permanent magnets – the key cleantech function of rare earth elements – which are used to transfer electricity into mechanical power and torque in an EV motor.

As trade tensions over clean technologies intensify between China and the US and Europe, Western governments have spent billions in subsidies to develop their own critical mineral supply chains, from mining, to processing and manufacturing.

“Canada and our allies understand, and are concerned about, the risks entailed with this level of market dominance and are taking a range of measures to diversify production,” a spokesperson for Canada’s department of natural resources told Climate Home.

Ontario, Canada’s most populous province, is betting big on creating a supply chain for EVs, its mining minister George Pirie told Climate Home in an interview. And recycling companies like Cyclic Materials are set to play a crucial role by providing a source of rare earths much closer to home.

“If China embargoed rare earths right now, that would put us out of business. They are a critical part of the supply chain,” said Pirie. Canada is home to several advanced rare earth exploration projects. But to build its own supply of rare earth elements, Ontario wants to be able to recycle them from waste, he added.

That urgency is starting to pay off. Canada overtook China in February for the first time to claim the top spot in BloombergNEF’s Global Lithium-Ion Battery Supply Chain Ranking, an annual assessment tracking 30 countries on their potential for building supply chains for electric batteries.

The research organisation cited the Canadian industry’s environmental, social and governance credentials, its integration with the US automotive industry, and consistent manufacturing advances, despite China holding the strongest established supply chain.

Kingston’s ambitions

“Canada will never be the cheapest country to produce a battery, but it will be the greenest,” Abdul Razak Jendi, sustainable investment manager at the Kingston Economic Development Corporation, the municipality’s sales and marketing arm, told Climate Home.

Operating from a smart downtown office building on the city’s main commercial drag, Jendi’s group is working to attract companies processing critical minerals to set up in Kingston. His co-worker, Shelly Histwood, calls these processing firms the “missing piece” for the EV supply chain. The region expects to create 1,500 new clean energy jobs in the next five years, she added.

“Geography plays a critical role” in the city’s rare earths recycling success, Jendi said, as Kingston sits between Canada’s capital Ottawa, its financial hub in Toronto, and the auto manufacturing belt in southern Ontario. It is close to the US eastern coast, and has shipping access to international markets via Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River.

Historic by Canadian standards, the city with a population of less than 300,000, which briefly served as the territory’s capital in the 1840s, doesn’t seem like an obvious place for refining and processing critical minerals.

But when EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen visited Canada last year to discuss the energy transition with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, Kingston was a key point of call for talks on critical mineral supplies and cleantech innovation.

How it works in the lab

Among the companies focused on critical minerals that have set up shop in Kingston is Ucore.

The publicly-listed Canadian firm opened a demonstration plant in the city in December with help from KPM, the chemical development company that supports others in the industry, including by providing facilities and personnel.

Ucore tackles what its chief operating officer Mike Schrider called “the most difficult element of the rare earths supply chain”: separating the rare earths from each other, and the materials they are found with.

Because rare earth elements are so similar to each other at a molecular level, separating them is a complex process, said Jonathan Leung, a frontline engineer at Ucore’s facility. Yet, each one has specific uses. Terbium, for example, is needed to create stronger alloys for EV motors.

This type of separation technology isn’t new. Comparable processes are used for extracting copper or uranium, and the “basics aren’t so different from decaffeinating coffee,” said Robert Teuma-Castelletti, a chemist at the facility. But applying the technology to rare earths is novel, he added.

Despite tough competition from China, Ucore hopes Kingston’s support for the industry will help it break into the rare earths supply chain. With scale in mind, the company is building a major new facility in Louisiana, US, which it hopes to have up and running by 2025-26.

A startup ecosystem

A short drive away, in a dilapidated industrial building in central Kingston, a team of chemists and startup entrepreneurs are trying to kick-start more innovation on critical mineral processing and recycling.

A man pores over plans for the future RXN Hub

Inside, construction workers in hard hats pore over blueprints as ceiling tiles and drywalls are removed as part of a full retrofit. RXN Hub aims to transform the building into a one-stop shop for new Kingston-based clean technology companies, particularly those working on the recycling of critical minerals, said Sebastian Alamillo-Falkenberg, RXN’s executive director.

“Our goal is [to achieve] 15-30% of recycled rare earths in the next 10 years as a stopgap until the [mining] supply chain can be built out in North America,” Alamillo-Falkenberg told Climate Home while touring the construction site.

From left to right: RXN HUB executive director Sebastian Alamillo-Falkenberg, Andrew Creese and Marc Froment of Modern Niagara, RXN HUB director of commercialisation Morgan Lehtinen, RXN HUB communications associate agent Karleigh Young at the future site of RXN HUB.

Cleantech industries are bringing talent into the city and helping convince graduates from the local Queen’s University to stick around a town that lacks the lure of Toronto, New York or Silicon Valley.

That influx is changing more than the city’s business environment. “When I was a kid in Kingston, I was aware of my skin colour,” said Alamillo-Falkenberg. “Now I fit in.”

Costing more than CA$10 million (USD $7m), RXN’s lab aims to be something of a co-working space for green technology startups. “There are no other facilities in North America with this kind of turn-key piloting,” said Alamillo-Falkenberg.

Battery business

While companies like Cyclic Materials and Ucore are working on technologies to recycle and process rare earths for EV motors, others around Kingston are building up a battery supply chain.

Surrounded by farms 25 kilometres outside the city, heavy machinery is clearing ground for Umicore’s new battery materials plant. Slated to start production in late 2025, the sprawling facility is set to be the first-of-its-kind in Canada.

The Europe-based company with operations around the world produces the materials used to make cathodes – the positive side of rechargeable lithium-ion batteries. The company described the facility as completing “the missing link in North America’s EV battery value chain, from natural resources to EVs”.

Recycling EV batteries themselves, however, hasn’t been a winning bet for Kingston so far.

Li-Cycle, a company which recycles lithium batteries, made waves when it announced plans for new production in the city in 2022. Trudeau and the EU’s Von der Leyen visited Li-Cycle’s operations during their tour of Kingston the following year.

Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, with Li-Cycle CEO Ajay Kochnar and executive chairman Tim Johnston during a tour of the company’s now closed facility in Kingston. Credit: Reuters/Lars Hagberg

The problem is that Canada alone doesn’t provide enough batteries to recycle to make the economics work, Kochhar said – a widespread issue in the battery recycling industry outside China. “It was an important testing ground, but now as we move forward, we are being judicious about economies of scale,” he added.

Instead, Li-Cycle is building a recycling facility in Rochester, in the US, which offers greater access to batteries for recycling as the country simply produces more of them.

Yet, concerns around scale haven’t deterred the early-stage startups of Kingston’s GreenCentre Canada lab, which are seeking to make their mark on the industry.

Unlike a traditional startup incubator, GreenCentre Canada provides hands-on technical services to validate technologies and grow companies. In the last year, it has helped several battery materials and minerals recycling companies test new technologies, said Tim Clarke, the group’s business development manager.

Inside the small lab, music blares on a boombox as a scientist with bright pink hair shakes a small test tube full of clear liquid.

Lab technicians at GreenCentre Canada

GreenCentre Canada has supported more than 30 cleantech companies in the last two years

GreenCentre Canada has supported more than 30 cleantech companies in the last two years, Clarke said, adding that commercialising a chemical process for rare earths recycling is far slower than developing an app or other digital activities traditionally associated with startups.

Clarke said Kingston’s emerging position as a cleantech hub is creating a broader buzz in the local community. “People at the hockey game are excited about all the investment,” he told Climate Home.

The quest for electrification and reducing reliance on fossil fuels comes with big challenges, he said. But recycling will be fundamental if countries are to avoid replicating the pollution and social conflict synonymous with a fossil fuel economy, he added.

“Electrification is not a panacea; as a chemist there are no absolutes,” Clarke said. “Extraction is extraction and it’s damaging. The use and re-use of materials makes sense from a circular economy perspective … and I think it’s very achievable.”

Chris Arsenault

Author

Ian Willms/ Panos Pictures

Photos & video footage

Chloé Farand