India

India wants its own solar industry but has to break reliance on China first

Monika Mondal

Mitul Kajaria

India

India wants its own solar industry but has to break reliance on China first

Monika Mondal

Mitul Kajaria

“Farming did not bring a lot of profit,” Ramzan told Climate Home News. But “the solar power plant promised jobs and prosperity”.

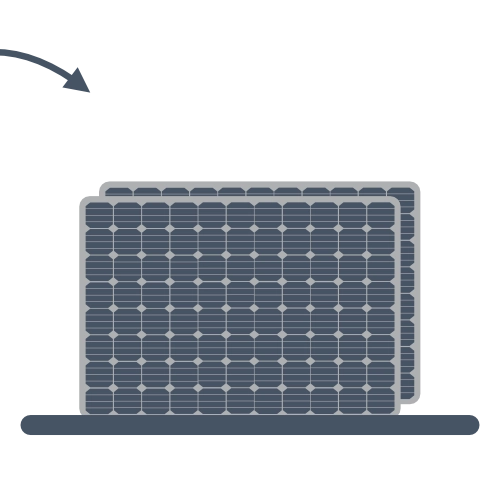

Three years on, Ramzan lives surrounded by a sea of solar panels and high transmission lines – with a front seat to India’s solar revolution.

One of the local solar parks belongs to Indian multinational conglomerate Adani, which is perhaps better known for its coal business. But most of the solar panels in the area are stamped with the same three words: “Made in China” – the world’s largest solar PV manufacturer, which dominates over 80% of all production stages.

However, future Indian solar parks may tell a different story. Faced with an accelerated solar build-out, the Indian government has set out to compete with Chinese solar cell and panel imports to meet its needs with made-in-India technology.

And the state of Gujarat – one of the most solar-developed in the country – is at the heart of India’s – and Adani’s – solar manufacturing efforts.

Solar factory

To meet a goal of reaching net zero emissions by 2070, India committed to triple renewable energy capacity to 500 GW by 2030 – with more than half expected to come from solar power.

Buoyed by rocketing solar panel demand, concerns over the concentration of the supply chain in China, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s vision for a “self-reliant India”, the government has taken steps to support domestic solar manufacturing.

“We aim that India becomes a leading manufacturer of solar modules. India is poised to become a global hub of renewable energy manufacturing,” renewable energy secretary Bhupinder Singh Bhalla told an event on clean energy recently.

Adani is one of India’s top solar panel manufacturers. Today, that process is equivalent to a large assembly line where components, largely imported from China, are fitted into solar cells and modules.

But the company is also among a handful of Indian solar manufacturers which are developing production capacity for components further up the supply chain.

Here, in 2022, the company made history when it produced India’s first silicon ingot by melting polysilicon at a high temperature.

Ingots are sliced into very thin layers to make wafers, which are processed into cells and assembled into solar modules.

Analysts at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (Ieefa) say India’s rise as a manufacturer of solar PV could one day make a dent in China’s dominance.

The institute foresees that India could become the world’s second-largest solar PV manufacturer by 2026 with a module production capacity of 110 GW – enough to make it self-sufficient and able to “aggressively” target the export market.

Between the US and China

Vibhuti Garg, Ieefa’s South Asia director, told Climate Home that India’s focus on solar manufacturing began in earnest following the Covid-19 pandemic.

Disruptions to global trade exposed the risks of concentrated supply chains at a time when energy security concerns had come to the fore.

“There’s been a big push to reduce reliance on Chinese imports because it can hamper energy security,” said Garg. But China’s two decade head start means India is still a long way from being able to compete with Beijing, she added. However, government support can help India scale its manufacturing.

Chinese government policies contributed to a dramatic fall in the cost of solar PV, which is now the cheapest source of electricity generation in many parts of the world and is helping the transition to clean energy.

But allegations of forced labour and human rights violations against Uyghur people in China’s Xinjiang region, which researchers estimate produces between one third and one half of the world’s solar-grade polysilicon, have led western countries and many solar developers to seek alternative supplies.

The US, for example, introduced a ban on imports of all products made in Xinjiang, unless it is proved they are not made with forced labour.

As a result, India’s solar module production capacity more than doubled between 2020 and 2023. Overwhelmingly driven by US demand, cell and module exports rocketed more than 1000% in April-July 2023, compared to the same period the previous year.

“Indian module manufacturers flourish through US exports, capitalising on the US-China trade tensions and government incentives,” explained Harshul Kanwar, a solar PV researcher who covers the Asia Pacific region for Wood Mackenzie.

Economic opportunities

Mundra was once a quiet village on the edge of the mangrove-lined Arabian coast.

People wandered and cattle roamed across the marshy land, and local communities harvested salt from the sea water, remembers Sajan Bhai Rabari, whose family has lived in the area for generations.

Today, the area looks like a large open-roof factory and lies at the heart of India’s energy transformation. It’s also here that Adani’s story begins.

In the late 1990s, Gautam Adani won the rights to operate the Mundra port, laying the foundation for his business empire. But it’s by importing and burning coal that Adani made his fortune, implementing a “pit-to-plug strategy” to control the supply chain from coal mines to power use – a model which the company aims to replicate in the solar industry.

Mundra’s industrial expansion has transformed many local people’s lives. Hostels have mushroomed along roads to accommodate the inflow of migrant workers from the east of the country, who found work at the port or nearby coal power plants.

Rabari, who works as a security staff at one of the coal plants, no longer lives in a traditional round mud house designed to stay cool in high temperatures, but built a modern home.

In recent months, Adani’s pivot to renewable energy projects have provided the conglomerate with a financial buoy amid a crisis which saw its stock tumble following accusations of accounting fraud and stock price manipulation. The group denies the allegations.

Locally, Adani’s solar plans have ushered in new economic opportunities.

Here, the company wants to develop an entire solar manufacturing supply chain. It already produces copper, aluminium, and glass, which are all needed to make solar panels.

Rabari told Climate Home that local people were finding jobs at nearby solar parks as security staff, drivers, cleaners, and grass-cutters for 10,000-15,000 rupees ($120-180) a month – above the minimum wage. But higher paying and skilled opportunities are lacking, he said.

In the nearest city of Bhuj, retailer Nitesh Patel, who buys solar panels from Adani and other manufacturers to sell to residential and commercial projects, is excited about made-in-India solar panels. His customers want to buy high-quality Indian products, he told Climate Home. “There is a lot of profit” to be made, he said.

The polysilicon challenge

Manufacturing solar modules from imported cells requires low capital expenditure and India’s cheap labour makes it well-placed to scale the industry, Satyendra Kumar, who began researching solar power in the 1980s and later spent years in the industry, told Climate Home.

But going down the supply chain to produce wafers, ingots, and polysilicon, “the process becomes capital intensive and the technology risk is high,” said Sunil Rathi, director at Waaree Energies, another leading solar panel manufacturer, which recently raised funds to make solar components.

The production process is also more energy-intensive and “the cost of energy and power in India is high. That is why India never really got into making polysilicon, ingots or wafers,” added Juzer Vasi, founder of the National Centre for Photovoltaic Research and Education, at the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay.

But “no matter how expensive, it makes sense for us to try to do it, purely from the point of view of energy security,” Vasi told Climate Home.

Still, this is a tall order. India’s production of polysilicon, ingots, and wafers must be scaled up from virtually zero at the start of 2023.

Despite a rapid acceleration in India’s manufacturing capacity, it remains heavily reliant on Chinese imports. According to BloombergNEF, around two-thirds of India’s imports of cells and 100% of wafers came from China since the start of 2021 and that is unlikely to change this year.

In Mundra, Adani has had to manage its expectations. A first goal to achieve 2 GW of ingot producing capacity by the end of 2023 was missed. But a spokesperson for the company said the facility would be operational by March, citing compliance issues. The target of producing 10 GW of fully Indian-made modules by 2027 “remains the ultimate goal,” they said. The company didn’t respond to several requests to visit its factory.

Government support

To boost domestic production, the Indian government launched a scheme that rewards selected solar manufacturers with funding for the production and sale of polysilicon, wafers, and solar cells and modules, which meet compliance checks.

Analysts at Ieefa have described the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme as “one of the primary catalysts spurring the growth of the entire PV manufacturing ecosystem in India”.

But industry insiders say incentives will need to be strengthened if India is to scale-up its manufacturing ecosystem over the coming years. It “excites the industry but it does not really assist them to set up a solar factory,” said Kumar.

Some have recommended expanding the scheme to include manufacturing machinery, upfront subsidies for setting up production units, and subsidised electricity tariffs.

With China mulling restrictions on exports of wafer production technology, Kumar is concerned that India might be shut-out of key technological know-how before it can scale its own production.

“Even with policies like PLI, the conundrum is how will producers make the upstream raw material if China does not help,” he told Climate Home, calling for stronger cooperation between India and western nations to diversify the solar supply chain.

But a glut in the market has seen the price of high-quality Chinese solar panels drop to a historic low. Even with the custom tax, imported Chinese modules remain slightly cheaper than Indian ones.

Earlier this year, a policy requiring all government energy projects to only use solar cells and modules from an approved list of Indian manufacturers was postponed until the end of March 2024, giving time for local production to catch up with the pipeline of projects.

Solar industry leaders have raised concerns that the lack of maturity of domestic solar production, the curb on imports, and growing exports to the US at the expense of domestic use could make it more difficult and expensive for India to meet its renewable energy goals.

As solar panel manufacturer Bluebird Solar put it in a blog post: “There is still a long way to go in terms of promoting domestic manufacturing and ensuring the successful execution of existing solar projects. Only by tackling these challenges head-on can India truly harness the potential of solar energy and achieve its ambitious renewable energy targets in the years to come.”

Main image: Women walk inside a solar park near Mundra,Gujarat, to fetch water / Mitul Kajaria

Monika Mondal

Mitul Kajaria

Chloé Farand