Chile

‘The state doesn’t want to know’: Doctors raise alarm on children’s health crisis in Chile’s copper heartland

Doctors are accusing Chilean authorities of turning a blind eye to rocketing cases of autism in the country’s copper-mining region, pointing the finger at the industry powering the energy transition

Ignacio Conese

Author & Photographer

Chile

‘The state doesn’t want to know’: Doctors raise alarm on children’s health crisis in Chile’s copper heartland

Doctors are accusing Chilean authorities of turning a blind eye to soaring cases of autism in its copper mining region, pointing the finger at the industry critical to the energy transition

Ignacio Conese

Author & Photos

In the waiting room of doctor Iván Silva’s medical centre, Nadia Saavedra and her husband Claudio sit quietly as their three-year-old son Pablo attends his regular physiotherapy session.

When Pablo was a year old, they began noticing he wasn’t developing like other children his age. He didn’t speak and couldn’t maintain eye contact. Tests confirmed their fears: Pablo had severe autism.

“The dreams, the expectations you have for your child – all of that is shattered,” said Claudio. “But I still hold onto hope that one day I’ll wake up and hear him say ‘dad,’ or ‘I love you’.”

Pablo is among a growing number of children diagnosed with autism to have come through the doors of Silva’s practice in the city of Calama, in the heart of Chile’s copper mining region of Antofagasta.

Like other medical professionals, the 71-year-old paediatrician suspects this worrying trend is linked to pollution from the vast open-pit copper mines that dominate this region in northern Chile – the world’s top producer of copper, a metal key to global electrification and the clean energy transition.

“When I started, I’d see one or two cases of autism a month. Today, it’s one per day, and the severity of the autism has increased,” Silva, the regional director of the Chilean Medical Association, told Climate Home News. Genetic conditions, respiratory and skin issues are also becoming more common among his younger patients, he said.

Silva is part of a group of medical practitioners raising the alarm about soaring numbers of children in the region being born with severe autism and neurodivergent conditions.

Environmental factors have been found to influence the onset and severity of autism, and medical professionals have called for more research into the impacts of copper mining on the health of local people, especially pregnant women and children. But lack of funding and limited access to laboratory facilities have so far thwarted efforts for comprehensive research.

“The state doesn’t want to know what’s happening here,” said Silva. “There’s no intention to investigate whether what we’re seeing is linked to mining. There are no research institutes, almost no universities involved and not enough doctors in Calama.”

Claudio and Nadia Saavedra in the waiting room of Iván Silva’s medical centre in Calama

Paediatrician Iván Silva

Climate Home’s repeated efforts to contact the Chilean government were met with a wall of silence. Neither the mining, health nor environment ministry nor Antofagasta’s regional government responded to requests for comment for this story.

In a statement after a 2023 visit to Chile, including to Calama in the north, David R. Boyd – the UN’s special rapporteur on human rights and the environment at the time – wrote that his conversations with “concerned individuals” had revealed “glaring long-term violations of their right to live in a clean, healthy and sustainable environment”.

“In many cases, these violations have endured for decades, leaving people disempowered, disheartened, and without hope,” he added.

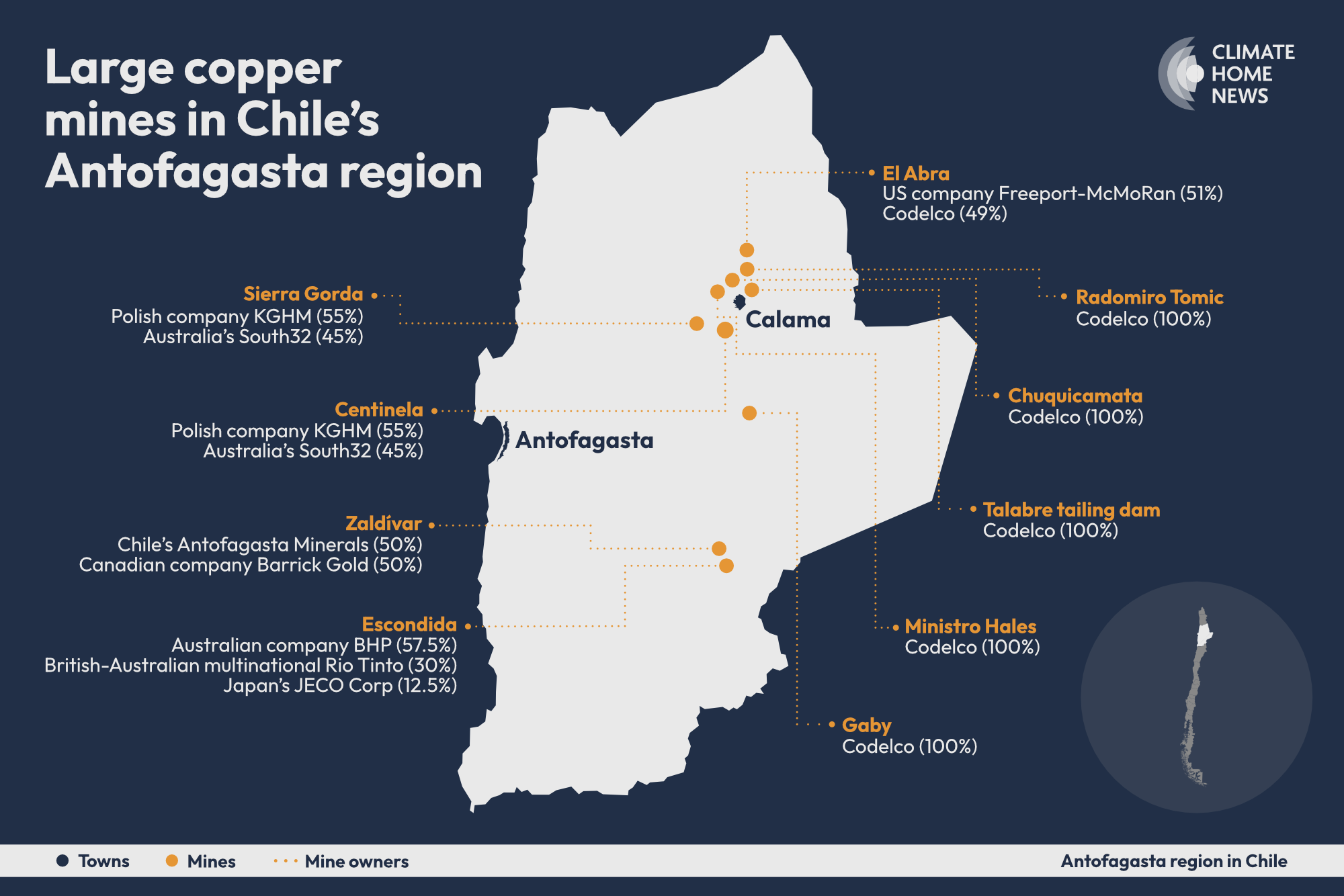

Chile’s copper hub

Copper is the foundation of the Chilean economy. Antofagasta’s copper mining industry, which dominates the livelihoods of the region’s nearly 700,000 people, is known across the country as El sueldo de Chile – “Chile’s salary”.

In recent years, the South American country has been responsible for close to a quarter of the world’s copper production. And global demand for its resources has never been so high. Between 2019 and 2022, Chile’s copper exports to China – by far its largest export market – grew by more than 30%.

A highly conductive metal, copper is critical for the transition from fossil fuels to clean sources of energy. It is used in virtually all electricity-related technologies the world needs to decarbonise power, transport and heating systems and curb climate change.

In fact, cleantech manufacturing is driving copper demand faster than production can keep pace with. Electric vehicles require up to four times more copper than traditional cars in their motors, wiring and batteries, while solar and wind energy projects need around six times more copper than fossil fuel-based systems.

But more than a century of intensive and large-scale copper mining in Antofagasta has left a trail of environmental destruction, including air and water pollution, with severe consequences for human health.

Calama has faced the environmental toll of mining for decades

The region has the highest cancer mortality rate in the country. The incidence of lung cancer is nearly three times the national average.

Studies have found that people in Calama and the city of Antofagasta, the regional capital, are exposed to dangerous levels of air pollution, mainly due to dust from nearby copper mines and the transport of copper concentrate, which contains high levels of heavy metals.

In 2009, the government declared Calama “saturated” with air pollution particles in breach of the country’s legal limit.

According to the World Health Organisation, long-term exposure to pollution particles can cause cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, including cancer.

Children, whose brains, lungs and other organs are still developing, are particularly vulnerable. In recent years, research has associated prenatal exposure to high levels of air pollution and toxic metals with the risk of children developing autism.

“No one here is safe from exposure. It’s impossible to live a completely healthy life with air as polluted as ours,” said Silva. “The damage is evident, particularly for children,” he added.

Claudio, a subcontracted miner at Chile’s state-owned copper mining company Codelco, told Climate Home many of his colleagues’ children have also been diagnosed with autism. “We share therapist recommendations, advice, or sometimes just listen to each other,” he said.

His son Pablo is among more than a hundred children on a waiting list for a space at Calama’s only public sensory room that supports the development of autistic children.

Doctors have suggested that leaving the city might improve Pablo’s health. But the family lacks the connections and resources to move. “We’re scared,” said Claudio.

‘Trading health for money’

Nestled in the barren and desolate Atacama desert, Calama is the nerve centre of Chile’s vast copper mining industry.

Situated at 2,400 metres above sea level, Calama was once an agricultural oasis, fed by the Loa River, the largest waterway cutting through this arid expanse.

Today, the city of nearly 200,000 residents sits alongside a massive industrial copper mining complex, where most of the Antofagasta region’s 126,000 mining-related jobs are concentrated.

The Ministro Hales mine is located 10km north of Calama

A train serving mining operations across the region

Codelco, one of the world’s top copper producers, operates three massive mines around Calama, including Chuquicamata, the second deepest open-mine in the world. Its colossal crater, visible from space, accounts for more than 40% of Codelco’s annual copper production.

Each morning, Andean winds blow white dust from blasted rock in mining pits and off the back of copper-carrying trucks into Calama city, where it settles, irritating residents’ eyes and throats.

“Winds in Calama are predictable,” explained Reinaldo Díaz Duk, who runs Calama’s newly established independent air-quality monitoring station. “Most mining activity happens east of the city, so when those easterly winds start, a thick, white cloud of dust from the mines settles over the entire city for hours.”

Born in Chuquicamata to a family of miners, Duk spent two decades working for a company that provided air pollution monitoring services to Codelco until he was laid off in 2015. In 2023, Calama residents won agreement from the city to set up a monitoring station with municipal funding to ensure trustworthy data, free from potential manipulation by the state mining company.

Reinaldo Díaz Duk operates Calama’s independent air monitoring station

At its worst in the early 2010s, air pollutant particles in Calama peaked at 40% above Chile’s legal limit, Duk told Climate Home.

Recent data from the independent monitoring station shows the air quality has improved since then, although the reasons for this are unclear. But air pollution remains slightly above what Chile deems to be safe levels – themselves far less stringent than international norms.

“Living here, you always wonder when the tests will come back bad, when I’ll get cancer. Every family here has someone with cancer,” said Duk.

Mining executives “come here and ask: ‘What’s the source? What’s the contaminant?’ But everyone knows they are trading health for money,” he added.

In a statement, Codelco insisted there could be “multiple factors” for the increase in autism cases.

The company has committed to bring down concentrations of air pollution particles in the communities neighbouring its operations within Chile’s legal limit by 2027.

“In the case of operations located in Calama, we are committed to ensuring a 20% reduction by 2027, specifically incorporating new dust suppression technologies and improving our adverse weather detection system,” it said. This includes solutions to control emissions during the crushing of rocks and transport of copper, it added.

In its 2023 sustainability report, Codelco says it has created an air quality model for Calama and is taking measures such as sweeping and washing the dust off the streets.

From Chile to the world

From Calama, copper concentrate is brought on trucks to the port of Antofagasta, where it is shipped to the rest of the world, and mostly to China, the juggernaut for manufacturing clean energy technologies.

In Antofagasta too, the storage and transport of copper concentrate disperses an oily black dust, which is difficult to wash off skin and clothing.

The international port terminal of Antofagasta, ATI, is located in the centre of the city

Analysis of dust samples collected in 2014 and 2016 revealed that the average concentrations of arsenic, copper and zinc within a kilometre of Antofagasta’s port were possibly the highest recorded in any city worldwide at the time – posing a considerable risk to people’s health.

And in this city too, evidence of rising autism diagnoses is rife. The Raíces School and Foundation, which opened in 2002 with 40 places for children with severe autism – and now runs three shifts of 40 students each – has seen its waiting list balloon to over 400.

“This building and its people are also contaminated by the port,” reads the sign on a building near the port of Antofagasta

The footprints left by a bird on a car covered in black dust in Antofagasta

Despite overwhelming demand, the school, reliant on public funding, is at risk of closure because of regulatory issues related to its current building. The school had been promised a new building, but the funds for this ended up involved in a corruption scandal and have been freezed since 2023. “It feels like [authorities] are waging a war against us,” the school’s founder, Gladis Zamudio, told Climate Home.

Doing nothing and allowing more children to be born with the condition isn’t an option, he said. “This reality is coming, and it’s one we can’t afford to overlook.”

Fabiana Vargas and her autistic daughter Roxana, who attends the Raíces School and Foundation

“No to the closure of basic education. No more exclusion,” reads the sign created by parents of Raíces School

Blowing in the wind

More than 11,000 kilometres away in Germany, Nicolás Zanetta-Colombo, a Chilean geographer based at the University of Heidelberg, has spent the past six years piecing together clues about the mining industry’s impact on the local environment in Chile.

With a group of Chile-based researchers, Zanetta-Colombo found evidence that the mining booms of the 1990s had increased levels of toxic metals in trees around the mining hotspots.

Tree rings corresponding to growth during peak copper production years revealed increased levels of mining-related metals, Zanetta-Colombo told Climate Home in a phone interview.

More recently, the team found that mining dust is carried by the wind up to 70 kilometres away from mining operations – a finding researchers say challenges the narrative pushed by authorities and Codelco that the high concentration of toxic metals in the area stems solely from natural causes such as soil leaching.

“Now the question is what happens to the people? How could this chemical imbalance be affecting their health, particularly children, who are the most vulnerable?” Zanetta-Colombo asked.

Mining companies “seek a social licence to operate, but there is no real accountability for the impacts [of their activities].” Corporate social responsibility has been reduced to building a football field, a park or a community hall, he added.

A playground built by Codelco on the outskirts of Calama, with the mining waste mountain from the Ministro Hales mine in the background

“I was born here in a family of miners. But this isn’t a nice place to live,” Cristian told Climate Home at a skate park in Calama close to the Ministro Hales mine

In April, Máximo Pacheco, a former energy minister who is Codelco’s chairman, told local media that Zanetta-Colombo’s study contained “exaggerations”.

Codelco, he said, is “taking charge of all the impacts that our activity has because Chile is a mining country and mining has an impact, so our responsibility is to take charge of that in a responsible manner.”

Monitoring toxic air

Codelco has been confronted with the consequences of its mining activities before – but its efforts to make amends have been judged insufficient by Chile’s legal system.

In the early 2000s, the company had to relocate an entire town built for workers at its Chuquicamata mine because of high levels of toxic dust. The town of Chuquicamata was officially abandoned in 2007 and its inhabitants rehoused in Calama.

Two years later, monitoring data from stations operated by Codelco showed that levels of polluting PM10 particulate matter – particles smaller than 10 micrometres in diameter that can pass through the nose and throat and enter the lungs – were above the country’s legal limit.

The government required Codelco to present a plan to address the pollution. The company finally published its response in May 2022 – 13 years later.

But environmental and resident groups accused the company of omitting readings from air monitoring stations and dismissed remedial proposals to clean the dust from the streets and plant trees as inadequate.

A local environmental group took Codelco to court and won. In June 2023, Chile’s top environmental court annulled the plan. The community has been waiting for new pollution clean-up proposals since.

In a statement, Codelco said a new air pollution reduction plan is being developed in a process led by the environment ministry. The state-owned company said it has committed to reducing particulate matter pollution in Calama by 500 tons annually until 2026 and is continuously monitoring air quality.

The Talabre tailings dam near Calama, a reservoir for mining waste and the largest of its kind in Chile, is undergoing its ninth expansion.

Paediatrician Pamela Schellmann and paediatric neurologist Jaime Gonzalez, of Antofagasta Regional Hospital, are members of the Chilean Medical Association. The professional body is one of the few major institutions in Chile to warn of the region’s public health crisis.

Over the past decade, the association, alongside civic groups like Este Polvo Te Mata, “This Dust is Killing You”, have pushed for stricter air quality regulations.

Chile’s legal limits for air pollutants are more lenient than those imposed in many of its key copper export markets, such as the European Union, and far exceed the World Health Organization’s recommendations.

Government fines, when imposed, amount to a fraction of companies’ profits. “They just pay the fines and keep doing the same thing,” said Gonzalez, calling for more severe sanctions and controls.

Paediatrician Pamela Schellmann and paediatric neurologist Jaime González

Schellmann blamed political inertia for the lack of action. But responsibility spreads wider than the Chilean government, she told Climate Home.

“It’s unacceptable that we’re still required to prove the health impacts of pollution in affected regions when this has already been confirmed by international studies and evidence from other mining areas,” she said.

What’s more, “the copper doesn’t stay in Chile”, she added. “There must be shared accountability, not only from the Chilean government but also from the international community. Why don’t Chileans have the same health standards as people in countries that are major buyers of the minerals extracted here?”

‘We are the sacrificed’

For those living in Chile’s copper heartland, Calama’s future is uncertain. Many fear the city will eventually face the same fate as the Chuquicamata mining camp and become uninhabitable. Some are already preparing to leave.

Aurelia and Calef Domínguez were among the first families to relocate from the abandoned town of Chuquicamata to a neighbourhood on the outskirts of Calama – just six kilometres from Codelco’s Ministro Hales copper mine.

Calef Domínguez wearing one of his protective mining masks

Calef and Aurelia Domínguez and her granddaughter Isabel watch the sunset from a viewpoint at the Ministro Hales mine

For two decades, Aurelia ran a business in Chuquicamata while her husband worked in the mine’s kitchen. Their eldest daughter was born with cognitive delay and a cleft lip and palate – a malformation which scientists in the US have associated with maternal exposure to air pollution.

But the family’s situation didn’t improve in Calama. Calef, who now works for a cleaning company employed by the mines, has developed respiratory, vocal and urinary issues. Aurelia suffers from worsening allergies and breathing difficulties, while her six-year-old granddaughter battles increasingly severe asthma attacks.

“Calama is a sacrifice zone, and we are the sacrificed,” Aurelia told Climate Home. The family has decided to leave the city and is hoping to settle in a southern mountain village with cleaner air.

“This feels like the second time we’re being displaced. Only now, we’re choosing to leave before they force us to,” she said.

The story was updated on 22 December 2024 to include Codelco’s response.

Main image: Isabel, her grandmother Aurelia Domínguez and her husband Calef look over the Ministro Hales copper mine

Ignacio Conese

Author & Photos

Chloé Farand